Cultivation Techniques, news

Part 3: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

Rice and Aquaculture

Four main rice-based farming systems in the Mekong Delta incorporate the capture and/or rearing of aquatic species (Xuan and Matsui 1998):

- rice-wild fish capture

- rice-aquaculture (freshwater fish, e.g., Pangasius spp.)

- rice-aquaculture (freshwater shrimp, e.g., Macrobrachium rosenbergii)

- rice-aquaculture (brackish-water shrimp, e.g., Penaeus monodon)

Wild fish capture has long been practised in the transplanted rice zones of the Delta, producing about 190,000 tons/year. Farmers dug ponds or ditches in the paddy fields to create refuges for fish during the rice-growing season. After the rice harvest, fish moved to the ponds where farmers could harvest them for home consumption. This system could yield 2–3 tons of rice/ha and 150–200 kg of fish/ha (Xuan and Matsui 1998). The average yearly consumption of fresh fish products was estimated at 21 kg per capita in 1995 (Rothuis 1998). Harvesting wild fish for sale provided additional income for most households. This system dominated before the rapid spread of HYV rice in the Delta (Xuan and Matsui 1998), significantly reducing wild fish capture. For example, the total fish catch in the upper delta decreased by one-third from 1995 to 2016.

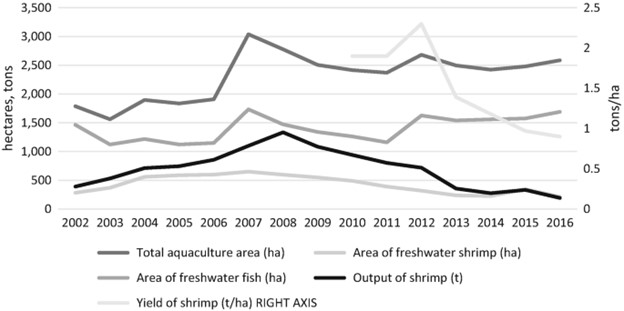

While traditional wild fish capture has declined, fish aquaculture has markedly increased (Fig. 17.7). This involves rearing fish in pens or floating cages and, increasingly, in ponds along the main rivers and canals using pelleted feed. Local catfish (Pangasius spp.) are the main species reared. The catfish industry began in the late 1990s in An Giang and Dong Thap Provinces in the upper Delta, and within a decade involved 800,000 farmers managing 6000 ha of ponds to produce 1.5 million tons, much of it exported to the US and European Union (EU). In the last decade there have been trade disputes with the US and concerns over quality in the EU, causing fluctuations in demand. Nevertheless, the area of freshwater fish aquaculture has continued to increase. For example, in An Giang Province, the area has increased from 1465 ha in 1995 to 1690 ha in 2016 (Fig. 17.8).

Systems combining rice with freshwater shrimp are mainly found in low-lying areas of the Delta. In the 1990s, farmers in Phung Hiep District, Hau Giang Province, in the Trans-Bassac Depression, began double-cropping with short-medium duration HYVs integrated with giant freshwater shrimp or fish such as snakehead and climbing perch (Xuan and Matsui 1998). The rice-shrimp farming system was introduced to An Giang Province in the Long Xuyen Quadrangle during the flood season of 2000. Tu Xang in Phu Thuan Commune of Thoai Son District cultured several hectares of shrimp and obtained a high economic return, thanks to good yields and a high price.Footnote6 In 2002, farmers in Chau Phu District followed this practice and cultured shrimp over 282 ha in the flood season, rotated with HYV rice in the dry season (Fig. 17.9). Nguyen (2014) found that the net return from one rice-shrimp cycle in 2006 was USD 2263, 85% of which was from the shrimp activity. This was much higher than the net return from double- and triple-cropping rice in An Giang (Table 17.5). Consequently, the provincial government formulated a policy to promote “flood-based livelihoods” through rice-shrimp systems (An Giang People’s Committee 2006). Farmers in Dong Thap Province in the Plain of Reeds followed those in An Giang, beginning shrimp culture in the flood season of 2004. In 2006 there were 146 ha of ponds, producing 230 tons. This increased to 700 ha producing 1200 tons in 2010.

Table 17.5 Economic returns to rice-freshwater shrimp farming in An Giang, 2006

From: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

| Parameter | Units | Rice | Shrimp | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Tons/ha | 6.76 | ||

| Price on sale | VND/kg × 103 | 2.269 | ||

| Total benefit | VND/ha × 103 | 15,338 | 102,540 | 117,878 |

| Total cost | VND/ha × 103 | 7437 | 57,790 | 65,117 |

| Net benefit | VND/ha × 103 | 7901 | 44,750 | 52,761 |

| Net benefit | USD/ha | 339 | 1920 | 2263 |

The area and output of freshwater shrimp increased markedly up to about 2008. However, production has declined significantly in the past decade due to chemical pollution from neighbouring HYV rice paddies, reduction in flood levels (the flood peak in 2015 was the lowest in 100 years), and unstable market prices. The area of shrimp ponds in An Giang peaked at 650 ha in 2007 and fell to 214 ha by 2016, while the average yield fell sharply from over 2 tons/ha in 2012 to be less than 1 ton/ha in 2016 (Fig. 17.8 above). With this decline in area and yield, total production in An Giang fell from 1334 tons in 2008 to just 194 tons in 2016. The same trends have occurred in both An Giang and Dong Thap Provinces.Footnote7

Rice combined with brackish-water shrimp was observed in five coastal provinces as early as the 1930s (Nguyen, H. C. 1994). In 1984, there was about 5000 ha of rice-shrimp farming (Xuan and Matsui 1998). At this time, the yield of shrimp averaged 640 kg/ha and the yield of rice ranged from 3.5 to 4.0 tons/ha (Xuan and Matsui 1998). In 2000, the total area of rice-shrimp was 71,000 ha, distributed across five coastal provinces: Ben Tre, Soc Trang, Bac Lieu, Ca Mau, and Kien Giang. This had increased to 153,000 ha in 2014 (USAID 2016). These semi-intensive rice-shrimp systems include one crop of wet-season rice and one or two crops of tiger shrimp or white-leg shrimp (USAID 2016). This system is very common in Soc Trang, Ca Mau, Kien Giang, Ben Tre, and Tra Vinh Provinces. Total brackish-water shrimp production was 65,000 tons with yields ranging from 300 to 500 kg/ha (USAID 2016). Preston and Clayton (2003) found that farmers’ incomes had improved significantly from adopting this system.

The rice-shrimp systems have several technical problems that threaten their sustainability. Nutrient use in rice-shrimp systems is less efficient than in dedicated shrimp grow-out ponds, causing low shrimp survival rates and low production (Dien et al. 2018). Leigh et al. (2017) found water temperature and salinity were too high in the dry season and dissolved oxygen was too low, causing low survival rate and low shrimp production. The rice crop was also affected adversely by high salinity levels (Leigh et al. 2017). Although rice-shrimp systems are economically and environmentally viable, farmers have tended to switch to intensive shrimp production systems (Preston and Clayton 2003).

Climate change poses new risks to rice-shrimp farming systems. Early saline water intrusion in November negatively affects rice yields while contributing to an accumulation of soil salinity over time (Preston and Clayton 2003; ACIAR 2016). The impacts of climate change have increased in recent years. Saline intrusion due to drought events occurs more frequently. The historical drought event in 2015 caused severe damage to rice, vegetables, flowers, fruit trees, livestock, buffaloes, cattle, and small fishponds. The coastal provinces were most affected, with rice, fruit, and aquaculture taking the brunt of the impact.

Conclusion

Rice-based farming systems in the Mekong Delta have been transformed over the last three decades due to farmer initiatives and government policy. Facing an urgent need to boost rice production after 1975, the government increased investment in water control and irrigation and promoted the intensification of rice farming through green revolution technology, leading to widespread adoption of double- and triple-cropping systems. With the expansion of irrigation and increased cropping intensity, the area of rice in the Delta increased from around 2.0 million ha in the immediate post-war decade to 3.2 million ha in 1995 and 4.3 million ha in 2016. The yield of the main wet-season (autumn) crop increased from about 2 t/ha in 1975 to 3.8 t/ha in 1995 and 5.3 t/ha in 2016 due to better water management, use of HYVs, and greater use of fertilisers. Total production of paddy rice was only about 4 million tons in 1975, increasing threefold to 12.8 million tons in 1995 and doubling again to 24.2 million tons in 2016. The increase is attributable in equal measure to the increase in planted area and the increase in yields. From being a net importer of rice in the 1970s and 1980s, Vietnam exported 1.4 million tons in 1989 following the first phase of intensification and market reforms. In 2016, exports totalled 4.5 million tons worth USD 2 billion, 90% of which was produced in the Delta. By any standard, this has been an amazing economic transformation.

However, the focus on rice intensification has shifted since 2000 as the impacts on farmer livelihoods and the environment have become apparent. Locking farmers into producing low-quality rice for the export market has not provided them with adequate returns, especially as both domestic and global demand have shifted in favour of higher-quality rice and more diverse diets. Specialisation in continuous rice production has also restricted the dietary diversity of rural households. Intensive use of fertilisers and pesticides has led to soil and water pollution and reduction in wild food supply. Moreover, the “total management” of hydrology in the Delta has had major impacts on water flows, sedimentation processes, aquatic species, and land-use options. The Delta is also highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including sea-level rise, increased drought and flooding, and saline intrusion, the latter affecting up to half the surface area.

In response, the government has progressively relaxed its restrictions on the use of paddy lands—originally conceived to achieve food security and maintain export earnings. Hence, rice-based farming systems have become more diversified in the last two decades, with the increased use of paddy lands for non-rice field crops, orchards, and freshwater and brackish-water aquaculture. Irrigated dry-season horticultural crops and productive and profitable orchards now abound in the Alluvial Floodplain. While the traditional inland fish catch has declined, the production of freshwater fish in ponds, especially local catfish, has developed into a major export industry in the upper Delta. Freshwater shrimp, however, after a rapid increase since 1990, appears to be in decline. In the Coastal Complex and the Ca Mau Peninsula, brackish-water shrimp culture has had a longer and more successful history, though it is facing challenges due to disease outbreaks, market fluctuations, and climate change.

The most recent indication of the shift in policy was the November 2017 resolution in support of sustainable development strategies for the Delta. These strategies include (1) promotion of high-quality rice, (2) reduction in the area planted to rice, (3) further diversification of farming systems, and (4) promotion of agro-ecological and organic agriculture. Targets have been set to increase the quality rather than the volume of rice and to diversify rice-based farming systems to make the best use of each agro-ecological zone in the Delta. Even traditional floating rice is being encouraged in the remaining deep-flooding pockets. Reduction in the area planted with rice is intended to help counter the overuse of chemicals in the paddy field ecosystem while opening further opportunities for the diverse range of crop, livestock, and aquatic products that are increasingly in demand in Vietnam’s cities. Promotion of integrated (or agro-ecological) rice-based farming systems is intended to provide the basis for more profitable and sustainable rural livelihoods in the Delta, with greater adaptability to changing markets and climate.

By Nguyen Van Kien, Nguyen Hoang Han & Rob Cramb

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-0998-8_17#Sec1

Read more:

- Metabolic turnover rate, digestive enzyme activities, and bacterial communities in the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei under compensatory growth

- Data, AI & seafood retail

- Investigating the effects of ammonia, nitrite and sulfide on Pacific white shrimp juveniles

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt