Cultivation Techniques, news

Part 2: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

The Intensification of Rice Farming

Khmer farmers cultivated rice in the Delta for perhaps 2000 years (Chap. 1). From the eighteenth century, Vietnamese farmers occupied the Delta under the expanding Nguyen dynasty and began to extend the paddy area (Xuan and Matsui 1998; Le Coq et al. 2001). Traditionally, farmers settled along the river levees and along sand ridges in the coastal zone. The typical farm comprised a homestead (usually with livestock), ponds (used for aquaculture or as wild fish refuges and for domestic water use), dykes and gardens for trees and cash crops, and paddy fields for rice cultivation (sometimes combined with fish or shrimp culture) (Xuan and Matsui 1998). In some systems, farmers dug ditches, used as refuges for wild fish, and raised beds alongside for growing annual crops such as sugarcane (Nguyen, H. C. 1994).

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, local rice varieties were cultivated in the wet season on the Alluvial Floodplain, while floating or deep-water rice was cultivated in the flooded zones such as the Plain of Reeds and the Long Xuyen Quadrangle (Le Coq et al. 2001; Biggs et al. 2009).Footnote1 After harvesting floating rice in December, farmers planted field crops such as mung bean, sweet potato, and maize, harvested in February or March (Xuan and Matsui 1998; Nguyen, H. C. 1994). Traditional, photosensitive varieties were cultivated in most areas of the Delta (Nguyen, H. C. 1994; Xuan and Matsui 1998). Early maturing varieties were cultivated in the Coastal Complex to permit harvesting before November when saline water intruded into the paddy fields. Medium-maturing varieties were grown in the tide-affected Alluvial Floodplain where water levels were difficult to control. Late-maturing varieties were cultivated in low-lying areas at risk of flooding. Floating or deep-water rice was mostly cultivated in the depressed zones where flooding in the wet season was inevitable—the Plain of Reeds and the Long Xuyen Quadrangle (Nguyen, H. C., 1994; Nguyen and Howie 2018).

The development of the Delta for rice-based farming systems can be divided into three stages: (1) adapting to existing conditions, (2) semi-control, and (3) total control (Le Coq et al. 2001; Kakonen 2008; Biggs et al. 2009; Vormoor 2010). For the first 200 years of settlement by Kinh farmers, there was little or no infrastructure for rice farming, other than the canals that farmers progressively constructed. Farmers cultivated only one rice crop per year where conditions were suitable, whether traditional wet-season rice or floating rice. They also harvested wild fish in the paddy fields during the wet season and planted dry-season vegetable crops (Vo 1975; Nguyen, H. C. 1993).

In the second stage, from the mid-1970s, irrigation infrastructure was developed, permitting the intensification of rice production using modern varieties (Le Coq et al. 2001; Kakonen 2008; Biggs et al. 2009). A single crop of local rice continued to be cultivated under rainfed conditions on higher land, while single- or double-cropping of modern varieties was introduced across the Delta where low dykes and irrigation infrastructure had been constructed. Many farmers accessed irrigation water using locally developed, portable, axial-flow (or “shrimp-tail”) pumps (Nguyen, V. K. et al. 2016; Biggs et al. 2009).

In the third stage, following a 1996 government decision, increased investment in raising dykes and extending internal irrigation canals enabled widespread triple-cropping of rice (Yasuyuki 2001; Biggs et al. 2009; Nguyen, V. K. et al. 2016).Footnote2 For example, farmers in Cai Lay District of Tien Giang Province began triple-cropping in the late 1990s (Berg et al. 2017). An Giang and Dong Thap Provinces also started to raise dykes to enable triple-cropping, with the greatest progress after 2000 (Nguyen et al. 2016). The central government offered direct financial support to provinces, districts, and communes to build dykes to increase the extent of triple-cropping even in provinces subject to wet-season flooding. The area of irrigated land increased from 52% of the Delta in 1990 to 91% in 2002 (CGIAR 2016).Footnote3

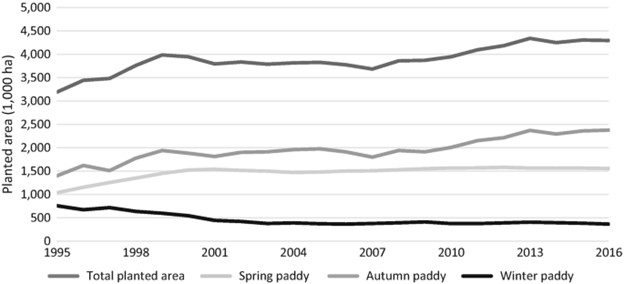

With the expansion of irrigation and increased cropping intensity, the area of rice planted in the Delta increased from 3.2 million ha in 1995 to 4.3 million ha in 2016, an annual increase of 1.4% (Fig. 17.4). Most of this increase came from the main wet-season (autumn) crop, the share of which increased from 44% to 55%. Farmers tended to replace the dry-season winter crop with an HYV crop in spring. The winter crop fell to 8% of the total area while the spring crop increased from 32% to 36%, with the main increase occurring in the period 1995–2000. Farmers shifted from winter rice to other dry-season crops such as maize, sweet potatoes, cassava, and vegetables, or left the land idle in this season. In coastal areas, farmers shifted to brackish-water shrimp farming in the dry season.

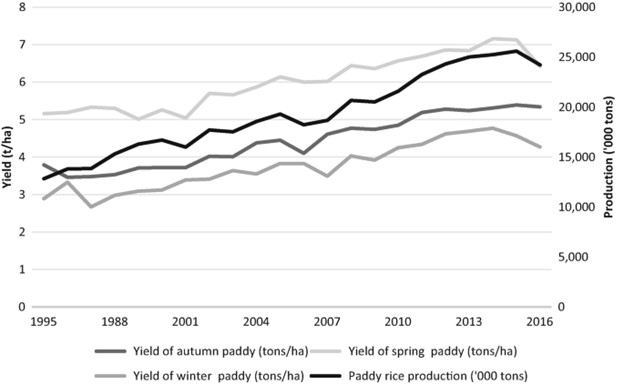

The total production of paddy rice has doubled from 12.8 million tons in 1995 to 24.2 million tons in 2016, an annual increase of 3.2% (Fig. 17.5). The increase in production was about equally due to the increase in planted area and an increase in yields. The yield of the main autumn crop increased from 3.8 t/ha to 5.3 t/ha, that of the spring crop from 5.2 t/ha to close to 7.0 t/ha, and that of the winter crop from 2.9 t/ha to 4.3 t/ha (Fig. 17.5). The yield increase in all seasons was attributable to better water management, use of HYVs, and greater use of fertilisers..

Despite this growth in area, yields, and production in the Delta, the rice sector faces several challenges (Nguyen, D. C. 2011). The focus has been on producing high-yield but low-quality rice, especially for the export market, with consequent low farm-gate prices (Demont and Rutsaert 2017). The use of inputs has increased, resulting in increased yields, but the net returns to rice farmers remain low (Berg et al. 2017). The use of fertiliser increased from 40 kg per ha in 1976–1981 to 120 kg/ha in 1987–1988 (Xuan and Matsui 1998) and reached over 600 kg per ha in 2015 (Nguyen et al. 2018). The application of pesticides increased three to six times from 2000 to 2015. The cost of these inputs has also increased, adding to the cost-price squeeze farmers are facing.

Rice production in the Delta also faces a series of interconnected environmental problems. The intensification of rice cultivation in the last 15 years has led to an increase in soil and water pollution from the overuse of agricultural chemicals (Nguyen, D. C. et al. 2015; Berg et al. 2017), and reduction in wild fish supply (Nguyen et al. 2018). Moreover, the Mekong Delta is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including sea-level rise, increased flooding, and saline intrusion, particularly in the Coastal Complex and the Ca Mau Peninsula (Dasgupta et al. 2007; Phạm and Furukawa 2007; MONRE 2009). Recent evidence shows that saline intrusion is having adverse impacts on both rice and rice-shrimp farming systems (Mainuddin et al. 2011, 2013; Ling et al. 2015; Thuy and Anh 2015; USAID 2016; Leigh et al. 2017; Stewart-Koster et al. 2017).

Diversification of Rice-Based Farming Systems

Farmers in the Delta have always combined other livelihood activities with rice production, giving rise to a range of rice-based farming systems in the different agro-ecological zones. With the trends in rice production described above and official encouragement to diversify production, a range of farming systems have been developed since the 1990s (Bosma et al. 2005; Tong 2017). The Delta now has seven dominant rice-based farming systems (Xuan and Matsui 1998):

- rice-rice-rice

- rice-rice

- rice-upland crops

- rice-livestock

- rice-wild fish

- rice-freshwater aquaculture

- rice-saline aquaculture

In addition, there has been a widespread conversion of paddy land to orchards in the Alluvial Floodplain. Trends in farming systems over the past 40 years are summarised in Table 17.3.

Table 17.3 Trends in farming systems in major landform units, 1976–2016

From: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

| Landform unit | Landform sub-unit | Farming system | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper floodplain | Natural levees | House-garden + winter-spring upland crops

Winter-spring rice + summer-autumn rice Winter-spring rice + summer-autumn jute Winter-spring upland crops + summer-autumn rice |

Increased

Increased Decreased Increased |

| Back swamp | |||

| Open floodplain | Floating rice + upland crops

Winter-spring rice Pineapple + cashew nut |

Decreased

Decreased Decreased |

|

| Closed floodplain | Summer-autumn rice + winter-spring rice

Floating rice + yam + local rice Melaleuca + bees + fish |

Increased

Decreased Decreased |

|

| Tide-affected floodplain | Natural levees and back swamp | Home compounds and orchards

Local rice + upland crop Summer-autumn rice + winter-spring rice Summer-autumn rice + local rice Winter-spring rice + spring-summer rice + summer-autumn rice |

Increased

Decreased Decreased Decreased Increased |

| Freshwater broad depression | Local rice

Sweet potato + autumn-winter rice (HYVs) Summer-autumn rice + winter-spring rice |

Decreased

Decreased Increased |

|

| Broad depressions | Broad depression | Summer-autumn rice + local rice

Local rice Autumn-winter rice (HYVs) Melaleuca trees + fish + bees |

Decreased

Decreased Increased Decreased |

| Coastal complex | Coastal flat | Wet-season rice (HYVs)

Local rice mixed with HYVs Autumn-winter rice (HYVs) + shrimp Summer-autumn rice after ridge flushing Coconut garden + fish + shrimp Upland crops + orchards on ridges |

Decreased

Decreased Increased Decreased Decreased Decreased |

As described in the previous section, double- and triple-cropping of rice have expanded mostly in the Alluvial Floodplain and in the adjacent broad depressions. Systems alternating rice and upland crops have expanded on the natural levees and back swamps of the upper floodplain and on coastal sand ridges. Rice-livestock farming systems, in which the paddy fields are used for rice while ducks, chickens, pigs, cattle, or buffaloes are raised in the home yard, are found in most zones of the Delta (Xuan and Matsui 1998). The rice-wild fish farming systems are found in the Ca Mau Peninsula and in the Long Xuyen Quadrangle and Plain of Reeds. Farmers cultivate only one local rice crop from May to December and harvest wild fish from paddy fields and canals during the cropping season. The rice-freshwater aquaculture (fish and freshwater prawn) systems have mostly expanded in Tien Giang and Can Tho Provinces in the tide-affected Alluvial Floodplain (Berg et al. 2017; Håkan 2002; Xuan and Matsui 1998). From 2000, with greater flood control, the rice-freshwater shrimp system was extended into the deep flood areas of An Giang and Dong Thap Provinces (the Long Xuyen Quadrangle and the Plain of Reeds) (Nguyen, V. K. 2014). Rice-brackish water shrimp farming systems have evolved over 80 years and are found in the coastal provinces of the Delta (Xuan and Matsui 1998; USAID 2016). Farmers cultivate one local rice crop in the wet season, when rainfall and freshwater flows enable salinity to be flushed out of the paddy fields, and modify the fields to culture brackish-water shrimp in the dry season. The main rice-based systems are discussed in more detail below.

Rice and Upland Crops

As described above, farmers traditionally planted field crops in upland plots in or near the homestead. In recent years, farmers have begun to allocate paddy land to these crops in some seasons, thereby increasing and diversifying their incomes. This trend has recently received encouragement from the government, which was previously intent on retaining all paddy land in the Delta for rice production. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) announced a land-use plan for 2014–2020 that mandates more flexible use of paddy land (Table 17.4). The plan encourages provinces to shift from rice to maize, soybean, sesame, vegetables, flowers, animal feed, and aquaculture. In total, the plan envisages a reduction of 316,000 ha of rice (7% of the 2013 rice area), mainly in the dry season, and an equivalent increase in non-rice crops, over half of which is to be taken up by maize (83,000 ha) and vegetable and flower crops (87,000 ha). More importantly, the government issued a resolution in 2017 to develop strategies for sustainable and climate-resilient development in the Delta.Footnote4 This resolution provided the basis for reducing the extent of triple-cropping of rice and further diversifying cropping systems.

Table 17.4 MARD land-use plan for paddy land in Mekong Delta for 2014–2020 period

From: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

| Crop | Area in 2013 (ha × 103) | Planned change in land allocation, 2014–2020 (ha × 103) | Area in 2020 (ha × 103) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Autumn | Winter | Total | |||

| Rice | 4338 | (160) | (129) | (28) | (316) | 4022 |

| Maize | 40 | 29 | 52 | 1 | 83 | 123 |

| Soybean | 2 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 23 |

| Sesame | 29 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 25 | 54 |

| Vegetables and flowers | 254 | 50 | 34 | 3 | 87 | 341 |

| Animal feed | 7 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 24 | 31 |

| Rice and aquaculture | 174 | 5 | 8 | 42 | 54 | 228 |

| Other | 53 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 22 | 75 |

Source: Approved land-use plan for changing cropping systems on rice land in the 2014–2020 period, MARD 31 July 2014

Farmers have developed appropriate rice-based cropping systems depending on local hydrological, soil, and topographical conditions. Two common patterns that have emerged are (1) one crop of rice followed by one crop of maize or sweet potatoes or several crops of vegetables and (2) two crops of rice followed by one crop of maize or sweet potatoes or one crop of vegetables. From 1995 to 2016, the area of maize has increased from just over 20,000 ha to nearly 35,000 ha, and the area of sweet potatoes has doubled from about 10,000 ha to 20,000 ha (General Statistics Office 2016). The area of all types of vegetables increased sharply from under 20,000 ha in 2000 to over 45,000 ha in 2011.

Rice and Livestock

Pigs are an integral part of farming systems in the Delta. Small-scale pig raising is very common—about 70% of smallholders own a pigpen, raising several pigs—while some operations raise several thousand head (Huynh et al. 2007). This activity creates employment for household members and provides a major source of income (Huynh et al. 2007). Farmers face market and disease risks, causing the number of pigs to fluctuate as prices vary and outbreaks of diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease or swine influenza occur. Nevertheless, total numbers in the Delta increased from 2.4 million in 1995 to 3.8 million in 2016.

Farmers traditionally raised chickens and ducks inside the homestead for both meat and eggs (Xuan and Matsui 1998). They were fed with rice, food waste, and local aquatic animals such as fish and snails. Each household raised small numbers of chickens and ducks for home consumption, or up to several hundred for sale. Some specialised, large-scale farmers raised up to several thousand head. However, the bird flu epidemic in the mid-2000sFootnote5 had a negative impact, with many small-scale farmers ceasing to raise poultry. The number of poultry in the Delta dropped sharply from 51.5 million in 2003 to 31.4 million in 2005. Nevertheless, medium- and large-scale poultry farming has increased dramatically since 2005, with total numbers reaching 64.7 million in 2016 (General Statistics Office 2016).

Before the 1980s, cattle and buffaloes were used for draught power, both ploughing and transportation (Xuan and Matsui 1998). However, following the doi moi reforms, most farmers have replaced buffaloes with two-wheeled tractors imported from Japan and China. Consequently, the number of buffaloes in the Delta has declined dramatically, from 113,000 in 1995 to 40,000 in 2001, with slower decline thereafter to 31,000 in 2016 (General Statistics Office 2016). In contrast, the number of cattle increased sharply, from 150,000 in 1995 to 680,000 in 2006, and continues to hover around 700,000. The primary use of cattle is now for commercial beef production, with high demand in nearby Ho Chi Minh City. Rice-growing households fatten up to ten cattle in sheds in the house compound (Fig. 17.6). Farmers grow forage grasses or use rice straw as forage, and also buy imported soybean cake.

… To be continued …

By Nguyen Van Kien, Nguyen Hoang Han & Rob Cramb

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-0998-8_17#Sec1

Read more:

- Good Shrimp, Bad Shrimp: How Shrimp Farming Practices Impact The Environment. (Part 1)

- Good Shrimp, Bad Shrimp: Is Your Shrimp Free From Antibiotics? (Part 2)

- Giant river prawns: a fresh hope for Bangladesh’s aquaculture sector?

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt