Cultivation Techniques, news

Part 1: Trends in Rice-Based Farming Systems in the Mekong Delta

Rice-based farming systems in the Mekong Delta have been transformed over the last four decades. Needing to boost rice production after 1975, the government increased investment in water control and irrigation and promoted intensification of rice farming through green revolution technology, leading to widespread adoption of double- and triple-cropping systems. As a result, the area of rice increased from 2.0 million ha in the late 1970s to 4.3 million ha in 2016. The yield of the wet-season crop increased from 2 t/ha in 1975 to 5.3 t/ha in 2016. Total paddy production increased from 4 million t in 1975 to 24.2 million t in 2016, the increase attributable equally to the increase in area and the increase in yields. From being a net importer of rice in the 1970s and 1980s, Vietnam exported 4.5 million t worth USD 2 billion in 2016, 90% of which was produced in the Delta. However, the focus on rice intensification has shifted since 2000 as the impacts on farmer livelihoods and the environment have become apparent. Locking farmers into producing low-quality rice for export has not provided adequate returns, especially as demand has shifted in favour of higher-quality rice and more diverse diets. Intensive use of fertilisers and pesticides has led to soil and water pollution and reduction in wild food supply. Moreover, the “total management” of hydrology in the Delta has had major impacts on water flows, sedimentation processes, aquatic species, and land-use options. In response, the government has progressively relaxed its restrictions on the use of paddy lands and rice-based farming systems have become more diversified, with the increased use of paddy lands for non-rice field crops, orchards, and freshwater and brackish-water aquaculture. The current policy promotes high-quality rice, reduced rice area, further diversification of farming systems, and promotion of agro-ecological and organic agriculture.

Introduction

In this and the next three chapters, the focus shifts to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, which accounts for 15% of the Lower Mekong Basin by area and 27% of the total paddy area but in 2015 produced 48% of the Basin’s total rice output and about 60% of its rice exports (Fig. 17.1). Thus, it is indisputably the “overflowing rice basket” of the region. It is also overflowing in the sense that much of the Delta is naturally flooded in the wet season and has been subjected to major hydraulic works to permit intensive rice farming throughout the year. It is also under threat of sea-level rise. This chapter reviews the trends in rice-based farming systems in the Delta as a whole while subsequent chapters report on field studies in An Giang and Hau Giang Provinces in the upper and middle Delta, respectively. These studies examined the domestic rice value chain from input suppliers to consumers (Chap. 18) and the cross-border trade from Cambodia (Chap. 19). Chapter 20 examines the more specialised cross-border trade in sticky rice between Savannakhet Province in Central Laos and Quang Tri Province in the North Central Coast region of Vietnam (thus complementing the analysis of rice marketing in Savannakhet in Chap. 9).

Geography of the Mekong Delta

As a geographical unit, the Mekong Delta comprises a triangle of almost 50,000 km2 of mostly fertile alluvial and marine deposits extending from Phnom Penh in south-eastern Cambodia through southern Vietnam to the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. About 39,000 km2 or 78% of the total area lies within Vietnam. We use the term “Mekong Delta” in this chapter to refer to the Vietnam portion of the Delta. In this portion, canal construction, first for transport, then for irrigation and drainage, has been undertaken over the past two centuries, accelerating under French rule in 1910–1930 and again since the end of the Indochina War in 1975 (White 2002). The Delta now has over 10,000 km of canals and 20,000 km of dykes, profoundly altering the hydrology and agroecosystems of the region. About 90% of the cropland is now irrigated.

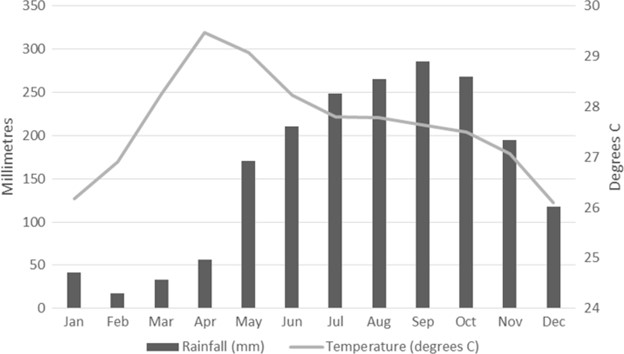

The climate of the Mekong Delta is similar to that of the Lower Mekong as a whole—a tropical monsoonal climate with distinct wet and dry seasons (Fig. 17.2). The wet season occurs from June to October, when monthly rainfall averages over 200 mm, and the dry season from December to April. Variation in temperature combined with the seasonality of rainfall gives rise to three rice-cropping seasons: (1) a cooler wet season from July to October (the main or “autumn crop”); (2) a cooler, late wet/early dry season from November to February (the “winter crop”); and (3) a hot, early wet season from March to June (the “spring crop”).

Wet-season flooding has been the dominant constraint in the upper Delta, with flood depths of more than four metres, while saline intrusion in the dry season is the major factor affecting land use in the lower Delta, limiting rice production to one crop per year (White 2002). Fertile alluvial soils make up about 30% of the Delta, mainly along the banks of the Mekong and Bassac Rivers, but acid sulphate soils occur in broad depressions over 40% of the area—about half the Delta is subject to saline intrusion. The Delta comprises six distinct agro-ecological zones with different potentials for rice-based farming systems (Nguyen, D. C. et al. 2007; Biggs 2015; Biggs et al. 2009; Fig. 17.1):

- The Alluvial Floodplain is the freshwater zone along the Mekong and Bassac (Hau Giang) Rivers, accounting for about 900,000 ha. The rivers and canals are tide-affected in the middle reaches of the floodplain, enabling farmers to irrigate and drain their land with the tides. This zone has fertile alluvial soils, and farmers practise intensive rice farming with two or three crops per year, while many have diversified into orchards, vegetables, and rice-fish aquaculture.

- Away from the main rivers, there are four large depressions. The Plain of Reeds in the north, accounting for about 500,000 ha, is the lowest part of the Delta at 0.5 metres below mean sea level. This zone floods in the wet season and features acid sulphate soils. Farmers traditionally planted deep-water rice in this zone but flood-control measures now permit intensive rice cultivation and rice combined with freshwater aquaculture.

- Similarly, the Long Xuyen Quadrangle, accounting for 400,000 ha, is subject to wet-season flooding and has acid sulphate soils. It was also a traditional area for deep-water rice, but since 2000, investment in flood control and irrigation has enabled more intensive rice production as well as rice-fish aquaculture.

- The Trans-Bassac Depression lies to the west of the Bassac River and accounts for about 600,000 ha. This zone also has acid sulphate soils but is not seriously affected by flooding or saline intrusion, providing good conditions for intensive rice production and other field crops.

- The Ca Mau Peninsula encompasses about 800,000 ha at the southernmost part of the Delta where the Delta is actively growing due to sediment deposition. This zone is subject to dry-season saltwater intrusion, limiting rice production to a single wet-season crop. Large parts of this zone have been developed for shrimp farming.

- The Coastal Complex includes about 600,000 ha of coastal flats and sand ridges, much of which is subject to saline intrusion, though coastal dykes have altered the hydrology. Along with the Ca Mau Peninsula, this has been the major zone for the expansion of brackish-water shrimp farming.

About 17.5 million people live in the Delta, including Kinh (90%), Khmer (6%), Hoa (2%), and Cham (2%) ethnic groups, accounting for one-fifth of Vietnam’s population. However, the population growth rate is only 0.3–0.5% due to out-migration (CGIAR 2016). Rice forms the basis of livelihoods for the millions of smallholders in the Delta, both as their staple food and as a major source of income. In 2016, Vietnam as a whole had 3.8 million ha of paddy land, producing over 40 million tons of unhusked rice, half of which came from the Delta. In the same year, Vietnam exported 4.5 million tons of milled rice worth USD 2 billion, 90% of which was produced in the Delta (Demont and Rutsaert 2017; Thang 2017). The planted area and yield of rice have increased over the past 20–30 years as irrigation and flood control have increased and as farmers have adopted high-yielding varieties (HYVs), increased fertiliser use, and small-scale mechanisation. In many parts of the Delta, farmers now cultivate three crops of rice per year.

However, the rice sector faces problems of low farm incomes and increased environmental hazards. Diversification of the farming system is now seen by both farmers and the government as a way to address these challenges. In 2000, the government issued the first of a series of policies to encourage farmers to diversify their production. Farmers responded by planting more non-rice crops on paddy land in the dry season, such as maize, vegetables, and watermelons, as well as combining rice with aquaculture. Fruit trees were also extensively planted on flood-protected upland areas (Nguyen, D. C. et al. 2007). In this chapter, we review the intensification and growth of rice production and assess the development of these more diversified rice-based farming systems.

Profile of Rural Households

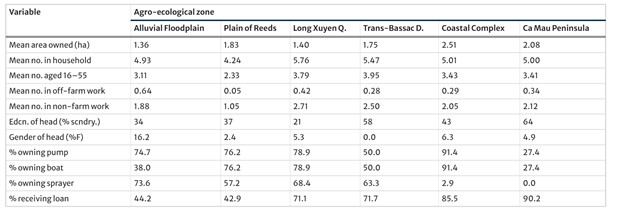

A household survey conducted in the mid-2000s gives a snapshot of rural livelihoods in the different agro-ecological zones of the Delta (Nguyen, D. C. et al. 2007). Some key characteristics of the average household in each zone are presented in Table 17.1. The average farm size was uniformly small, but lowest in the more productive Alluvial Floodplain (1.4 ha) and largest in the Coastal Complex (2.5 ha). Household size averaged around five members throughout the Delta, with an average of two to four members of working age. The proportion of working-age members engaged in off-farm labouring was highest in the Alluvial Floodplain (20%) but mostly below 10% in other regions. However, the proportion engaged in non-farm work was high across the Delta, ranging from 45% in the Plain of Reeds to over 70% in the Long Xuyen Quadrangle. The education level of the household head was similar across zones, with one to two-thirds having completed lower secondary school. Almost all household heads were men, but in the Alluvial Floodplain 16% of households were headed by a woman. The ownership of key equipment varied across the zones depending on variations in livelihoods. Pumps were an essential item for most households (75–90%) except in the Ca Mau Peninsula where there was less reliance on irrigation. Similarly, ownership of a boat was essential in the flood zones of the deep depressions and the Coastal Complex. Sprayers were owned by 60–70% of households in the major rice-growing areas but were less common in the coastal shrimp zones. The use of credit varied from around 40% in the Alluvial Floodplain to 90% in the Ca Mau Peninsula.

Source: Nguyen, DC và cộng sự. ( 2007)

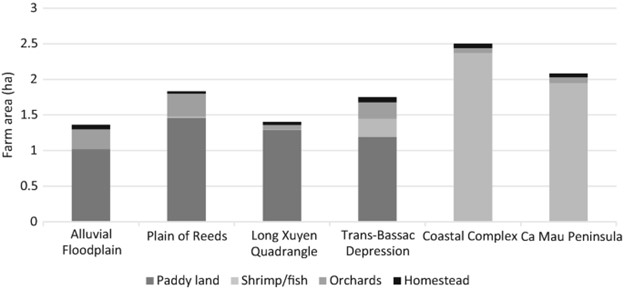

The different patterns of household land use are indicated in Fig. 17.3. Paddy land dominated in the Alluvial Floodplain and surrounding depressions, averaging between 1.0 and 1.5 ha. Orchards of 0.2–0.3 ha were also a significant feature of land use in these zones. However, shrimp and fish farms were the dominant land use in the Coastal Complex and the Ca Mau Peninsula, averaging 2.0–2.4 ha.

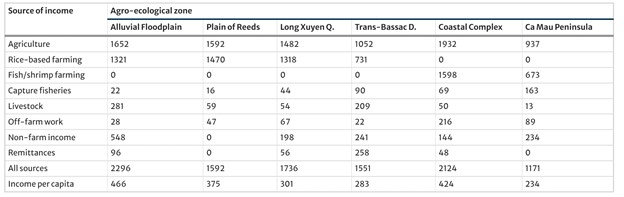

The land-use patterns were partly reflected in the sources and levels of income (Table 17.2). Farmers in the Alluvial Floodplain and the adjacent depressions (Plain of Reeds and Long Xuyen Quadrangle) obtained 80–90% of their farm income from rice and field crops, earning USD 1300–1500 in 2005. In contrast, farmers in the Coastal Complex earned 85–90% of farm income from shrimp and fish, with coastal farmers averaging USD 1700 from this source. Non-farm income was more significant for households in the Alluvial Floodplain, indicating greater livelihood diversification in this more accessible and densely populated zone. Overall, these farmers and those in the Coastal Complex obtained the highest incomes per household (USD 2100–2300) and per capita (USD 420–470). Those in the Ca Mau Peninsula were the poorest, with about half the mean income of the more prosperous zones.

Source: Nguyen, D.C. và cộng sự. (2007)

… To be continued …

By Nguyen Van Kien, Nguyen Hoang Han & Rob Cramb

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-0998-8_17#Sec1

Read more:

- Evaluation of single cell protein on the growth performance, digestibility and immune gene expression of Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei

- Data, AI & seafood retail

- Investigating the effects of ammonia, nitrite and sulfide on Pacific white shrimp juveniles

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt